On Friday, my friend Chersti posted a great blog article about successful love triangles, using the movie Casablanca to explain five guiding principles for awesome angst: equal screen time, winning moments, unknown outcome (as opposed to obvious outcome), equal chemistry, and character growth influencing choice.

My only question was . . . what do you do when things get more complicated, when there are more than three characters involved and some of the sides are unrequited (i.e. unequal chemistry)? Because I might sort of have that going on in my novel . . .

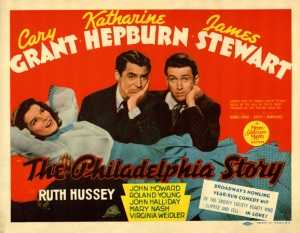

So, to copy Chersti’s great post, I thought I’d look at an old movie as well: The Philadelphia Story with Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, and Katherine Hepburn.

So, to copy Chersti’s great post, I thought I’d look at an old movie as well: The Philadelphia Story with Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, and Katherine Hepburn.

Things are complicated, all right. Cary Grant loves his ex-wife Katherine Hepburn, who thinks she loves her fiance “George Kittridge,” who worships Katherine Hepburn, who has an alcohol-induced fling with reporter Jimmy Stewart, who is infatuated by her but loved by “Liz” his photographer partner.

To sum up: Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart and “Liz” the photographer all suffer from unrequited love through a good chunk of the movie.

Also: it doesn’t feel like we’re ever really meant to root for George the fiance. The story sort of stacks the cards against him.

“George,” Cary Grant, Katherine Hepburn, Jimmy Stewart;

“Liz” and Jimmy Stewart

What do you do with that?

Some of Chersti’s principles still apply, I think. While there’s not much mystery about George losing in the end, there IS mystery on Katherine Hepburn’s end. She truly doesn’t know that she doesn’t love George; she has to figure it out through the course of the movie as she grows as a character and finally decides between three guys in the end.

And because Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart both have plenty of screen time and plenty of “winning moments,” there is a bit of a mystery about which of them Katherine Hepburn will choose. Both of them have proven to be equally worthy of her in different ways.

And because Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart both have plenty of screen time and plenty of “winning moments,” there is a bit of a mystery about which of them Katherine Hepburn will choose. Both of them have proven to be equally worthy of her in different ways.

But what’s especially great about the unrequited aspects of the triangle is that even if those poor characters aren’t stirring their intended’s heart, they are stirring the audience’s.

We feel so bad for Liz and admire her for the way she handles rejection. Our hearts break when Cary Grant watches Jimmy Stewart propose to Katherine Hepburn because we see the agony on Cary Grant’s face and have come to admire him as a character, too.

I think that often “chemistry” is something that those on the outside can see better than the people on the inside. It’s clear to the audience almost from the beginning that Katherine Hepburn doesn’t belong with George. It’s clear to the other characters, too. It’s also clear that Jimmy Stewart belongs with Liz. And while we wonder about Cary Grant because he’s the ex (read: failed once already), still the audience and the other characters realize he’s Katherine Hepburn’s match before her character does.

In that way the outcome is obvious, but it’s so clearly not obvious to the characters inside those relationships that the tension of the movie is created by wondering whether or not and how and how soon they’ll see things clearly.

And that’s sort of true to life, isn’t it? With my first boyfriend in college, when I would call and talk about him with my mom, she could tell without ever having met him that he wasn’t right for me. She was nice about it, just dropping subtle hints like, “Isn’t that kind of a red flag?” but the trick was that I had to grow and realize things about myself before I was ready to see what she saw and break up with the guy.

And that’s sort of true to life, isn’t it? With my first boyfriend in college, when I would call and talk about him with my mom, she could tell without ever having met him that he wasn’t right for me. She was nice about it, just dropping subtle hints like, “Isn’t that kind of a red flag?” but the trick was that I had to grow and realize things about myself before I was ready to see what she saw and break up with the guy.

Nicely, the things I learned from that experience helped me recognize my hubby when we found each other later on. Just like Katherine Hepburn’s character learns enough about herself to realize that she loves and needs and wants Cary Grant.

Ta da! Or really . . . ditto. Because it turns out that all I’ve done is reinforce Chersti’s post. Her five aspects seem to hold up even in complicated situations.

And maybe what I’ll add is that the most important chemistry of all for a character is with the audience. If the character gets enough screen time to shine with winning moments and to prove to the audience that he/she deserves a chance with his/her love, the unrequited aspect will just make us sympathize more, make us root for that character more, and make us hope that his/her love will treat him right by the end.

On the other hand — and here’s a whole different problem — what if the unrequitedness isn’t going to be remedied in the end? What if you’ve got an odd number of characters and one of them, like George, just obviously doesn’t fit in the match up?

That happens to be the issue in my WIP.

In The Philadelphia Story, the solution was to make George less likeable than the others. He’s an okay guy, but just okay. Not a Cary Grant or a Jimmy Stewart. And he doesn’t really get much screen time or any winning moments. By the end, in fact, his nobility of character is tested and he fails.

In The Philadelphia Story, the solution was to make George less likeable than the others. He’s an okay guy, but just okay. Not a Cary Grant or a Jimmy Stewart. And he doesn’t really get much screen time or any winning moments. By the end, in fact, his nobility of character is tested and he fails.

What if I don’t want to handle it that way? What if I want to let a certain character have winning moments, prove to be a great guy, etc, but his growth through the book teaches him that he’s not the right guy for the girl he’s pined after and he hasn’t met the right one for him yet? Maybe that’s where it does get complicated. How do you show that the growth is more important than being in a relationship?

Let me know your thoughts on any of this, including books or movies that do love dodecahedrons well.

I think that by having a character realize he isn’t the one for her, he has his most winning moment. The audience realizes that he is nobel and good. Especially if you end with him being hopeful and not all gloomy and why me. Hope for a happy end for him is enough for me. Just make sure the scene has enough emotional impact to be satisfying. 🙂

LikeLike

Great insights! I like that a lot and I think you’re right. I’ll have to incorporate that in my next draft.

LikeLike

Wow, it’s great to see my formula being applied — thanks for that. I think I might have to do another follow-up post on the third wheel, because there are so many areas to explore 🙂 But great job, Nikki. Hope you get it worked out in your manuscript.

LikeLike

Thanks for letting me steal your idea a little (okay, a lot). 😉

LikeLike

Omigosh- the Philadelphia Story is probably close to my all-time favorite movie ever. I’m constantly quoting it. And I totally get that moment at the end, when Jimmy proposes, and we see Cary’s face. That moment is only possible through everything that has led up to it, and if you do it wrong, it won’t pack the punch.

Excellent post!

LikeLike

Woo-hoo! I hardly ever meet anyone who has even seen this movie, but we feel the same way: it’s a quotable, all-time fave. And you are so right about the punch. Thanks for the comment! 😀

LikeLike

Great post. I’ll have to add it to my Netflix list. Thanks!

LikeLike

No problem. Hope you like it!

LikeLike